The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) confirmed the first case of human screwworm linked to travel within the United States. This marks a significant event, highlighting the potential for the spread of this parasitic infection, typically found in warmer climates, to previously unaffected areas. The confirmation underscores the importance of vigilance and the need for robust public health surveillance. While details surrounding the specific patient, location, and precise travel itinerary are likely being withheld to protect patient privacy, the confirmation itself raises several crucial points: Vector-borne disease spread: The case demonstrates the ability of disease vectors, in this instance likely a screwworm fly, to travel across state lines and infect individuals. This necessitates a coordinated response across multiple jurisdictions. Increased surveillance: The incident will undoubtedly prompt increased surveillance efforts to detect any further cases and to identify potential breeding grounds of the screwworm fly. This might involve intensified inspections at transportation hubs and increased public awareness campaigns. Treatment and prevention: While the screwworm infection is treatable with appropriate medical intervention, early detection is crucial for optimal outcomes. The HHS will likely emphasize the importance of seeking prompt medical attention for any unexplained wounds or skin lesions, particularly following travel to areas where screwworms are prevalent. The agency may also promote preventative measures, such as protecting exposed skin and using insect repellents. Climate change implications: The spread of screwworms into new areas may be linked to climate change, with warmer temperatures expanding the suitable habitat for these insects. This suggests the potential for future outbreaks and the need for proactive adaptation strategies. The announcement by the HHS warrants close attention. Further information, as released by public health officials, will be critical to fully understanding the extent of the risk and to inform preventative and control measures. The case serves as a potent reminder of the interconnectedness of global health and the potential for unexpected outbreaks, even within seemingly safe and well-established regions.

The first case of a New World Screwworm infestation in a human was confirmed in the U.S., according to the Department of Health and Human Services.

Travel-associated New World Screwworm was detected in a patient who returned to the U.S. from El Salvador, and was confirmed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention on Aug. 4, HHS spokesperson Andrew Nixon said in a statement to TheNews on Monday.

The CDC investigated the case in coordination with Maryland's health department.

"This is the first human case of travel-associated New World screwworm myiasis (parasitic infestation of fly larvae) from an outbreak-affected country identified in the United States," Nixon said, adding that the risk to U.S. public health is currently "very low."

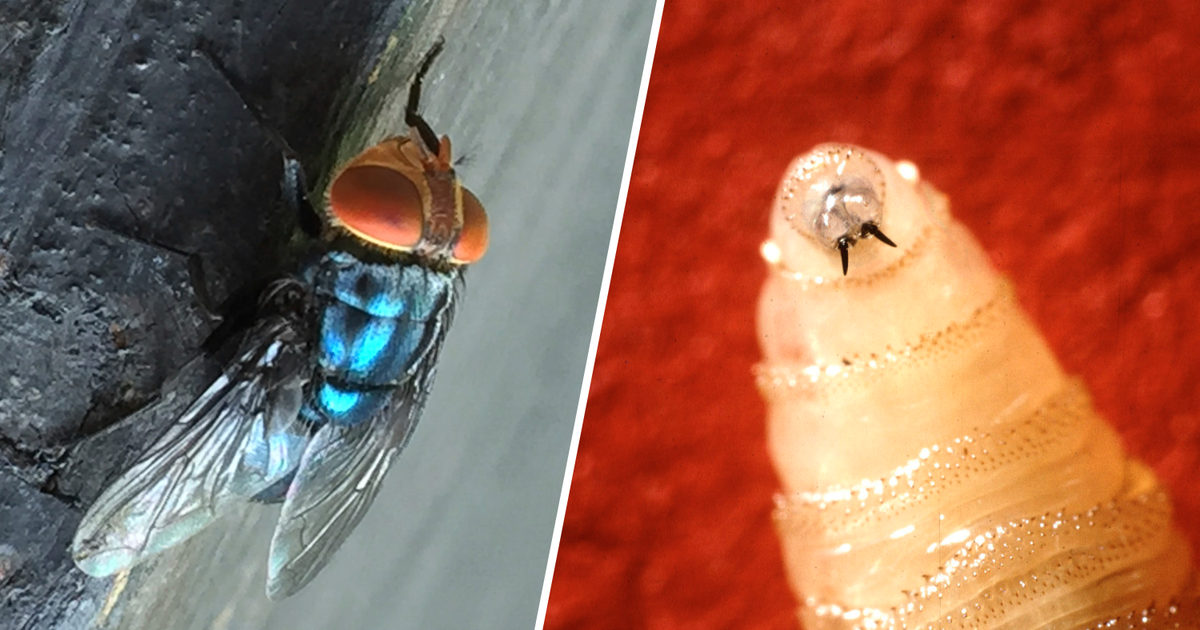

New World Screwworm myiasis is a parasitic infestation of fly larvae, or maggots, caused by New World Screwworm (NWS) parasitic flies, which feed on live tissue, the .

"When NWS fly larvae (maggots) burrow into the flesh of a living animal, they cause serious, often deadly damage to the animal," the says. "NWS can infest livestock, pets, wildlife, occasionally birds, and in rare cases, people."

The Texas Parks and Wildlife Department says NWS flies lay eggs in "open wounds or orifices of live tissue such as nostrils, eyes or mouth" — an infestation and painful condition, known as .

"These eggs hatch into dangerous parasitic larvae, and the maggots burrow or screw into flesh with sharp mouth hooks,". "Wounds can become larger, and an infestation can often cause serious, deadly damage or death to the infected animal."

It is usually found in South America and the Caribbean. Those at higher risk of suffering from the condition include people living in rural areas in places where NWS is endemic, and where livestock are raised, as well as people with open sores or wounds, and vulnerable populations, the CDC says.

There is no medication to treat it, according to the agency.

Late last year, for outdoor enthusiasts in South Texas after New World Screwworm was found in a cow in the southern Mexican state of Chiapas. The Texas Parks and Wildlife Department said New World Screwworm had been making its way further north through the Americas.

"As a protective measure, animal health officials ask those along the southern Texas border to monitor wildlife, livestock and pets for clinical signs of NWS and immediately report potential cases," the department said at the time.

In June, the U.S. government aimed at stopping the spread of New World screwworms in live cattle and other animal imports, including a plan to build an insect dispersal facility in Texas.